Building the BD-200

by Doug Walsh

by Doug Walsh

In late 1980, I was a 23 year old motorcycle mechanic at a large dealership near Cleveland, Ohio. I wasn't really looking for another job, but one day two different people showed me the same help wanted ad. The ad was looking for someone to help build a special high mileage vehicle based on a motorcycle.

I was known around the shop as sort of a "mad inventor" because I liked to build things. I called the phone number and showed up for the interview at Bede Industries in Cleveland.

I remembered Jim Bede from a second grade field trip to a local airport where he was working on the BD2 project.

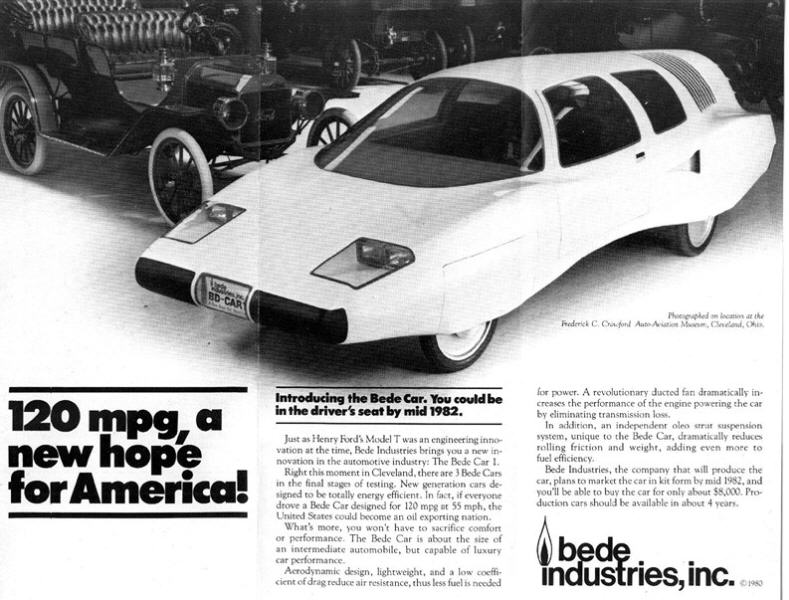

Today, he was working out of his cousin's business, where he just completed a ducted fan powered four wheel car. The idea was a 120 MPG automobile that would revolutionize the automobile industry.

Jim had arranged to borrow some shop space and was looking for part time help to do fiberglass work on his personal projects. He seemed happy to find a motorcycle mechanic and I explained that I modified my road racing motorcycle to include a rising rate linkage suspension, front anti dive brakes and rear brakes that forced the bike to squat for better weight transfer. I also mentioned I just finished a fiberglass body dune buggy.

I got the job and immediately started working part time in the evenings for a few weeks.

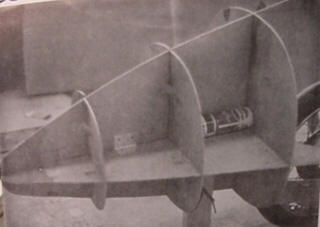

The Bede automobile was frequently demonstrated for investors. However, it was hard to start and didn't run perfectly, so I installed different carburetors and made a custom ignition advance unit to smooth out the idle and low speed performance.

It used a sawed off motorcycle engine with no transmission and a fixed advance ignition for aircraft use. I had to make an advance unit that ran backwards because they moved the ignition to the other side.

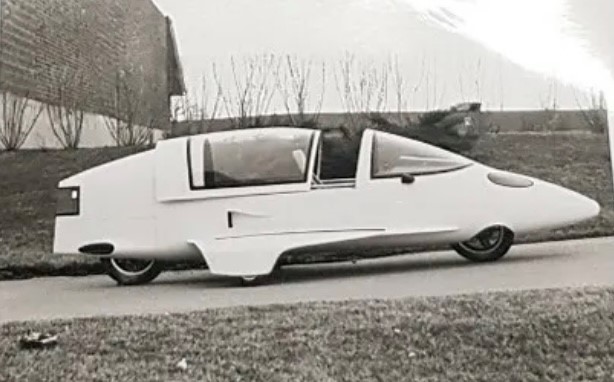

As I remember it, the car looked sexy, but was very impractical. It had very little static thrust so it couldn't climb a driveway, it would even get stuck if a small stone got in front of the tires. Of course it kicked up debris because you had to really gas it to get rolling. The chassis was weak and flexible with over half the weight of the vehicle on one skinny overloaded motorcycle wheel.

I think Jim's cousin put up the money and provided the space at his company in Cleveland. The current owner of the Bede Car is unknown.

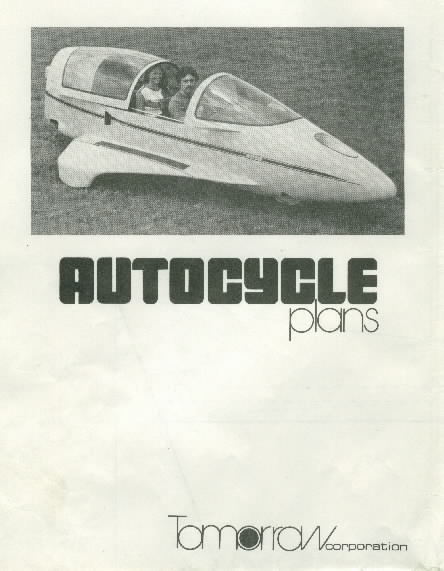

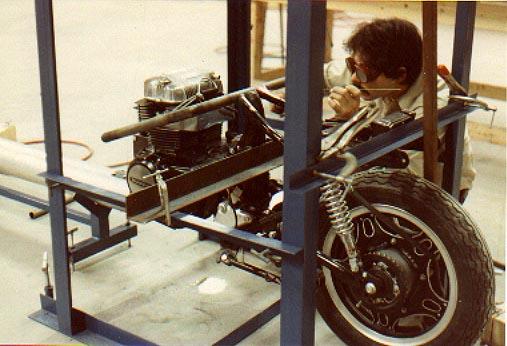

Jim hired me because of my motorcycle background. He soon found a used Honda 360 to use as a donor bike for his new Autocycle project. He also brought in talented ex BD-5 designer Paul Griffen. While Paul was drawing up the body shape, I gave the bike a good tune up, and then sawed it in half. The first prototype, designated BD200 was underway and the construction was documented in a set of plans that sold for $20.00. I think around 400 sets of plans were sold.

Jim brought in someone who could gas weld thin chrome moly tubing and we assembled the chassis in a few days.

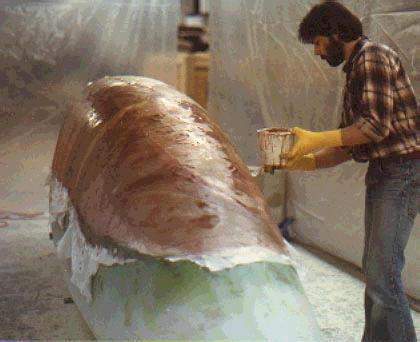

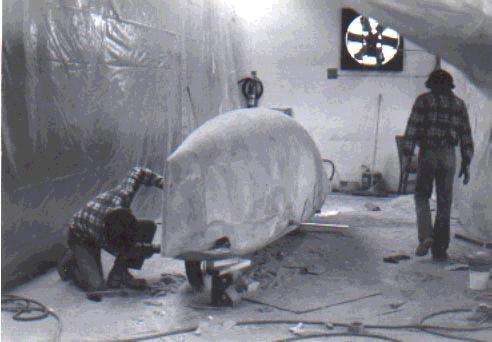

I then cut out templates from thin wood paneling and fixed them to the chassis so it looked like a dinosaur skeleton.

Urethane foam was used to fill in the spaces and the now famous pop cans were inserted into the nose and side beams for crash protection. The foam was sculpted down to the templates and we were ready for a "fiberglass party".

Jim, Paul, and myself worked late one night under the direction of his cousin's employee. I think his name was Bob and he also worked many hours to help us with body finishing and canopy construction. The four of us covered the considerable surface area with several layers of cloth and resin to form a hard shell. We now had something shaped like a vehicle in just over a month.

Much work remained however. The three of us were amateur fiberglass workers, so it took Bob and me several more weeks to fill in the cloth weave and all its irregularities with body filler. The two of us then hollowed out the foam interior and glassed the interior walls.

Jim Bede

supervised marking the canopy shape before cutting.

Now the pressure was on, I think Jim had to give up the shop space soon. He kept telling me that all we need is an aerodynamic shape that drives. I shouldn't get hung up on the details because we were just using this car for test data and then we would build another one.

I worked frantically to fabricate the steering and controls, and to hook up the fuel and electrical systems. After a quick paint job, it was ready for testing.

I learned a hard lesson there, because despite Jim's intentions, we dressed up that prototype and paraded it around for two years trying to find investors. When people saw the BD 200, they assumed it was our best workmanship, but they never knew how fast it was built. For all the exposure it got, I always wished we spent more time on it. However, prototype #1 started the ball rolling and the rest is history.

I want to thank Robert McRay for his monumental effort to salvage the BD 200 and his restoration of this small piece of automotive history.

Test results were needed to sell the project to investors. So once the prototype was finished, I quickly strapped myself in.

A short drive around the parking lot turned up a low speed wobble. This was cured with a steering damper and after somemore tweeking, off we went for a few days to the Transportation Research Center in Marysville, Ohio.

Jim's previous testing of the Bede fan car produced a claimed 117 miles per gallon and it only stood to reason that a smaller lighter car with less drag and a smaller engine should do much better. Today, I wonder if the BD200 designation was an optimistic prediction of 200 MPG?

We started out using the same fuel flow meter that was used on the fan car, but it was giving unstable readings. The meter would fluctuate between a high and low number such as: 70-200, 90-180, 80-160, etc..

We were confused, but Jim seemed willing to accept the high numbers and throw out the low ones because this fit his expectations. We were dealing with very low flow rates and the only way to be sure, was to run a lengthy test where we let fuel drip into a container and measure the time and volume of the fuel to compare with the flow meter readings.

Things grew tense and Jim didn't want to lose a day of expensive track time around the 7 mile banked oval, just to watch fuel dripping. I stubbornly insisted that we are wasting all of our time, if the flow meter is bad. No one told me, kids weren't supposed to question famous airplane designers.

To his credit, he never pulled rank on me, but graciously agreed to let me stay up all night with a stopwatch, watching fuel drip at different rates into a bucket. Our suspicions were confirmed and the flow meter was bad! I think we rented another one or just measured accurately to finish the testing.

I eagerly increased the speeds between official test laps and Jim had a talk with me explaining the aviation term, "pushing the envelope". He related how some test pilots have been known to explore higher performance levels without official authorization. Well, my current hobby was motorcycle racing, and my young ears just heard permission to go faster!

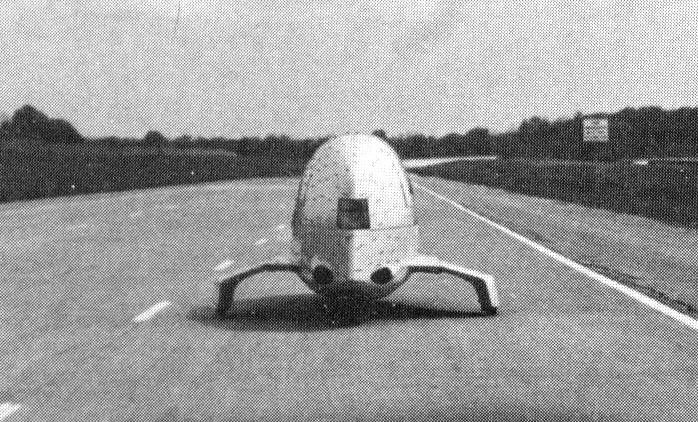

Rare photo on the test track.

Notice

the short strings attached to the body

to assist in the evaluation of airflow over the body.

I voiced my opinion before the car was built, that we should consider ways to make it lean into turns. The extreme time constraints prevented us from looking into this, and it never came up again. The early three view drawings showed the outriggers in a raised position so it wasn't ruled out completely. I had a folder of sketches and ideas ready just in case it ever came up again. I was always surprised how few customers seemed to care if it leaned.

I also worried about the durability of motorcycle wheels and tires when exposed to side loads, and the durability of brakes when you doubled the vehicle weight. Jim's answer: the production vehicle will weigh only 575 lbs. and the aerodynamic speed brakes would assist braking.

After the testing, Jim published a 31 page information manual that detailed his design objectives. He showed considerable restraint by publishing the fuel consumption at a little over 100 MPG. I later measured an unofficial 98 MPG during normal highway driving. As good as this sounds, it must have been difficult for him, because it cast doubt on his claims of 117 MPG for the larger and heavier Bede fan car he designed for his cousin. I respected him then for not exaggerating the facts, but things would change for the worse.

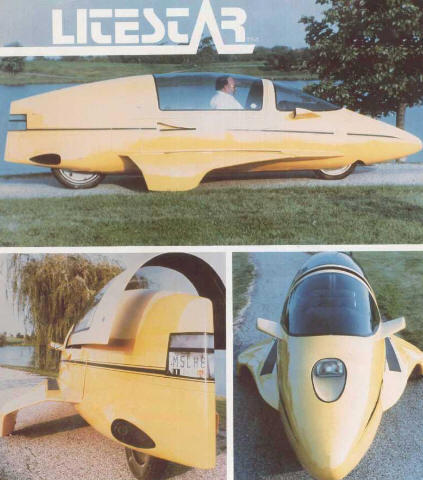

The funds began to run out and we had to move out of his cousin's building. While Jim worked on trying to raise additional capitol, I smoothed out the body some more and took it to Maaco for a bright yellow paint job.

I took some time off from the hectic pace and Jim promised to pay me back wages, as soon as he found funding and also agreed to pay me a 4% royalty on all plans sold. I'm still waiting for both. I think Paul Griffen also went back to a real job at that time?

Weeks (or months?) went by before Jim asked me to prepare the BD 200 for a cross country "Future Fuels" rally. After he gave me a signed I.O.U for the money owed, I was back to work. Like everything else so far, this had to happen in an impossibly short time period.

I first had to do a major repair on a cracked frame and then figure out how to make it run on some alternate fuel. We didn't have much time to research it, but we chose ethanol. I was lucky just to find some ethanol before we left.

We were off to Missouri to pick up a truck from the car dealer who was sponsoring us. I was supposed to convert the car to ethanol power in the back of the truck while Jim drove us to California. I read that you had to dramatically enlarge all of the carburetor jet sizes and air passages, so I brought extra carbs, jets, small drills and enough tools to build a new car by the side of the highway if needed. Its unlikely that this would have worked without more development time, but we never got a chance to find out. When we got to Missouri, the promoter skipped town and the rally was canceled.

Our sponsor for the rally was a colorful character who used to be a promoter for Evel Knievel. He was running for Sheriff of this small town and his hobby was drag racing cars. We had nothing to do so he signed us up for a big car show in St. Louis called "World on Wheels". I think he was the show organizer.

We tried to get some custom graphics for the BD 200 to promote the show, but couldn't quite do it in time. We were desperately late, so the promoter tore off the unfinished graphics, and told me to drive there as fast as I could. Since he was about to be sheriff, he said he would take care of any speeding tickets and even put his cute daughter in the back seat to give me directions. I was warned that he would be right behind me and I better not let him catch me.

Well, I can't even think up a fantasy that good! I was a young invincible motorcycle racer and I just had a future Sheriff order me to break the speed limit. I was gone before he could change his mind!

We drove the next half hour at speeds of 80 to 110 mph. This was rush hour traffic into St. Louis and I had a mission to accomplish that required some creative lane splitting. I thought.....When was I going to get another chance like this? And what kind of father would put his daughter in a homemade car with a stranger who raced motorcycles?!!

We were standing by the curb when he arrived. He said he averaged 90 mph and never even saw us. His brave daughter never screamed once.....or maybe she did and I couldn't hear it over the deafening interior noise.

After that ride I can't even remember the show, I think we just stayed out in front of the building. This job didn't pay much, but it had its moments!

The summer of 1981, Jim went to Africa for some kind of BD-4 business and left me with a half-baked design idea to build a simple running car chassis for third world countries. This project was for a friend of his and had to be finished in a month, another pressure job.

With no one to answer questions, I was told to just "wing it'. I had a nice workshop behind my parents house and worked hard once again to keep one of Jim's promises. The result was a running chassis for a car called the "Village Vehicle". It used a two cylinder 18 HP air cooled engine and a snowmobile torque converter. It barely resembled Jim's design, but the customer loved it.

Jim trailered the chassis to Washington DC and I followed him in the Autocycle. I promised to drive normal this time! I was always amazed at how many people have cameras in their cars, so I brought one just to take pictures of them gawking at me.

While we were there, I followed Jim to the Department of Transportation offices where he hoped to convince at least one D.O.T. employee that this was actually a three wheel vehicle.

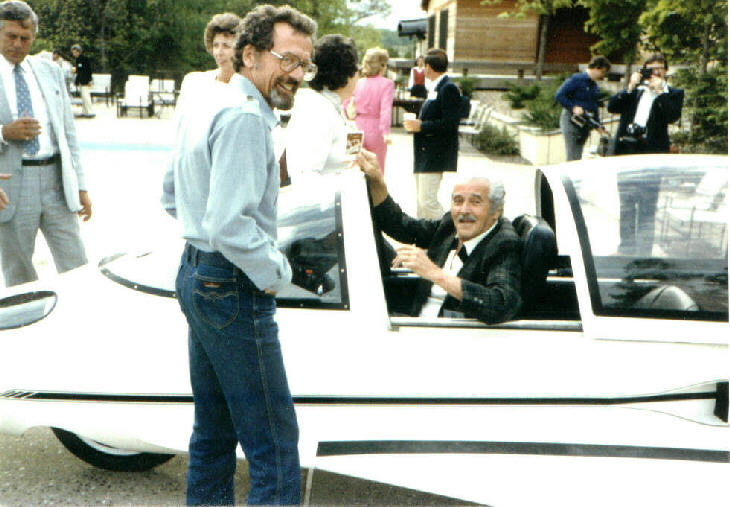

Always on the lookout for investors, we drove out of town to meet a member of the Dupont family at a small gas station for a demo ride in the BD 200. Apparently he forgot his checkbook!

At least I got to see the Smithsonian. I'll admit to feeling a little awed standing next to Jim Bede and looking at the first BD-5 prototype hanging from the ceiling. He later talked about donating the Autocycle prototype in order to take some huge R&D deduction on his taxes. I was just surprised he paid taxes!

For a long time I chose having fun over making money, but my parents urged me to consider paying them back sometime very soon, so I had to take a job as a service manager at another cycle shop.

A fall and winter passed, and I was getting used to the idea of a regular income. In the meantime, Jim kept the Autocycle at his house in Ohio and worked on finding an investor. In April 1982, I told him about an event I go to every year called "Bike Week" Its located in Daytona Beach Florida and is the world's largest gathering of motorcyclists.

75mpg City and 102mpg Highway

Apparently, Stan was impressed enough to buy into the project. Here we go again......

In May 1982, Jim convinced me to quit my steady job, uproot my life and move with him to Mundelein, Illinois where we would continue development of the Autocycle. I knew of his reputation with money, and he still owed me around $10,000 in back wages, so I got it in writing with a promise of steady income from then on. There was no timetable for repayment, just vague promises that the company would grow fast and I was in on the ground floor.

Oh well,.... at least I would get to drive the Autocycle from Cleveland to Chicago. I followed behind Jim's van and got 98 MPG.

We stayed at his friend's house in Illinois while he looked for a building and I looked for an apartment. I began to regret my decision when Jim couldn't come up with money right away. So much for a steady income I thought. It took a while to find a building, set up shop and buy tools.

I later heard that Stan Leitner invested $25,000 and I suspect we used that money to get started. Paul Griffen came to work and we were back in business.

The yellow prototype was kept busy giving demo rides to dealers and press people. I think it was that summer when Jim introduced me to the EAA airshow. The Experimental Aircraft Association holds the world's largest airshow in Oshkosh, Wisconsin each year and I loved airplanes. We trailered the car, but drove it around quite a bit when we got there. That was the first time I ever got stopped by police and he made us wait until a fellow officer showed up with a camera. I still got a ticket for something and Jim promised to pay it, months later, Jim was still promising to pay it!

When we arrived the gate worker wouldn't let us in. He must have been an old BD-5 customer? We had to wait in a cornfield until EAA founder Paul Poberezney showed up. I think they were old buddies and soon we were allowed in. After the BD-5, Jim didn't exactly have a good reputation with some people in this crowd and I suspect Paul Poberezney advised him to keep a low profile.

I new Jim couldn't do that, so I always worried about getting in the way of a fist meant for Jim Bede's nose. A couple of negative comments, but no confrontations arose. We mostly stayed on the fringes of the airshow.

Even as it was happening, I felt lucky to be a part of something exciting. Whatever you think of Jim Bede, he was a fun guy to hang out with. Always in a good mood and telling jokes, he could put anyone at ease and make them laugh. I grew up more mechanically inclined than socially adept, and now I found myself hanging out with a famous engineer who never got tired talking about machines. It sure beat my old job convincing stupid motorcycle customers that mixing oil with gas is not optional for two stroke engines.

Jim enjoyed food and got some strange satisfaction feeding a kid with a bottomless stomach. He paid for meals when we went on road trips so, I did my best to eat up all the back wages he owed me. Ahh.. Life was good. Paychecks became regular, we were building a second car, and Jim started finding money. While Paul Griffen and me were starting on the second prototype, Stan and Jim began looking for a manufacturer.

Stan Leitner was a real character that reminded me of Colonel Sanders and a Texas billionaire. He was a large person with a resonant voice and he wore white suits, smoked big cigars and drove a white cadillac convertible with bull horns for a hood ornament.

Pretty early on they found David Vaughn of Vaungarde in Owosso, Michigan and Jim became obsessed with a process called spray RIM (reaction injection molding). This was a promising new process where they would spray a chemical mix that reacted and cured on the mold surface to make body panels. It could be an inexpensive and fast way to get into production, and I think Jim liked the idea of being the first to use a new process to make his new vehicle.

The Propaganda begins...

Things were picking up steam now as the Bede/Leitner marketing team charged ahead. I understand they put out the first dealer newsletter in March 1982 promising delivery dates before we even set up shop!

At that point we had Paul Griffin working on the design and drawings with the help of a young engineer named John Kuczaj. They later hired a third draftsman named Irv Foote. We also hired a multi talented guy named Jed Richardson. I think he was supposed to work on the owners manuals, but he was artistic and had great hands, so I recruited him to help with the tedious job of making the master body pattern.

Tomorrow Corp. was pumping out brochures that promised a 575 lb. vehicle that would do 0-60 in 9.5 seconds with a 250 cc engine. The only car in existence had a 360 cc engine, weighed over 750 lbs. and did 0-60 in about 17 seconds. Was this a forecast of things to come??

The brochure listed imaginary prices and mentioned thousands of miles of grueling tests under all types of weather conditions. I must have been sick the day we did the grueling tests!

It was late summer now and the second dealer newsletter dated July 1982, claimed a company called Bass industries was tooling up and ordering inventory to start production in August and it could be late Oct before all customers received their cars. Ultimately that facility was supposed to produce an amazing 900 Autocycles (now called Litestars) per month with two assembly lines and three shifts.

The newsletter went on to say the vehicle exceed our expectations in various road and weather conditions. I must have missed those tests too! It even listed air conditioning as an option for $425. I thought,..hey if you're going to make everything up, you might as well give it cruise control!

The yellow prototype was still showing up in magazines and newspapers with claims like "production was scheduled for July 1982, but had to wait 2 1/2 months before the first cars rolled off the assembly line. Was I missing something here? Was there a parallel universe where a factory was cranking out Litestars. It sure wasn't on this planet!

Time for a reality check!

Four or five months after we opened our doors, our vast dealer network was expecting hundreds of cars to roll off the assembly line last month! The scary truth is that we had one tired prototype, a plaster body master and a partially built chassis for prototype #2.

Dealers kept wandering into the shop asking if their car was done yet. I wouldn't lie, so Jim had to keep people away from me. I thought, I've got to start looking for another job and visited a few motorcycle shops in the area. The gap between propaganda and reality was growing too fast.

As if this wasn't enough stress for us, Jim promised one dealer we would build him a custom machine in our spare time for $10,000 using an 1100 cc motor. I got the chassis built, but it was never finished.

What I thought was a good salary turned out to be sub minimum wages when you figured in the long hours. Finally it became obvious to everyone, that even without sleep, Doug couldn't build 900 cars per month! We better staff up fast!

We hired another shop helper (forgot his name) and Stan sent us his son in law Tony (forgot last name) to help out. It was pretty obvious that Tony was going to be Stan's eyes and ears. Maybe he didn't trust the information Jim was giving him. We welcomed all the help we could get and never hesitated to speak freely in front of his son in law. Tony turned out to be a great guy and helped tremendously in many ways. We kind of hoped he would communicate the truth to Stan, but the propaganda machine never slowed down.

It was complete chaos. Paul and I had many lunchtime gripe sessions complaining about the lack of organization and outrageous promises. Paul had been through this already with the BD-5 and pointed out many similarities. He commented that this was Jim's dream not ours, and we should walk away before causing any conflicts. Jim should be grateful for a dedicated friend like Paul Griffen. The pressure was unbearable, but I felt fortunate to be involved with more interesting and gifted people.

As time went on, Jim's dream would have an impact on thousands of customers, dealers and investors, not to mention myself. I was still prepared to walk away before causing trouble. It was never that clear cut though, I thought by being vocal, I could encourage positive changes. After all I had my life and money invested in this thing too. The project grew legs and ran away from Bede with less of his influence showing every day. I was becoming less concerned with offending Bede and more concerned for the unsuspecting customers.

By now it seemed like Jim and Stan had LiteStar deposits from every man, woman and child on earth. Rather than burden himself with delivering these cars Jim chose to start work on an ultralight aircraft project. He rented the building next door, found investors and pretty much abandoned the Litestar.

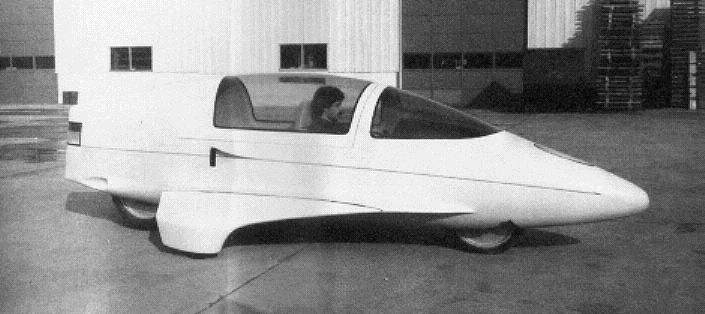

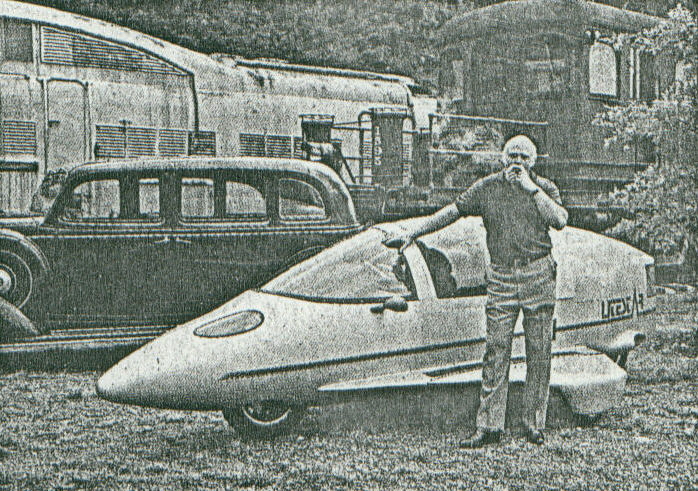

I always demonstrated the BD-200 to prospective investors because of its operating quirks. However, this photo shows Jim giving a reporter a rare demo ride at the first public showing.

While all this was happening, Vaungarde was struggling with the spray RIM process. Dave Vaughn seemed like a smart, honest person and he invested much time and money to develop this process. We saw many part samples, but they all had problems.

They were too flexible, so they added chopped fiberglass, which made them heavy with irregular wall thickness. This "unbreakable" material ended up being quite brittle while still being flexible and heavy. Vaungarde should get an award for their efforts, but the material still needed development time.

Jim finally relented and got us two sets of hand laid fiberglass parts to work with. He wouldn't let go of the RIM however, and ended up building a 250 lb. Ultralight that actually weighed 450 lbs. and sagged when left in the sun.

Help finally arrives!

We had more people now but our fearless leader was preoccupied with airplanes, so someone decided we needed a project manager. I was pretty numb by this time and thought it was too late to salvage the project.

Don Rudney was hired to perform a miracle and I felt sorry for him. He was a smart, clear thinking guy who actually asked for input and ideas instead of just issuing deadlines. Over the next month we dumped all of our problems on him, but he still showed up every day with the determination to succeed, and this boosted my morale. He cared, he listened and hopefully he had the authority to make positive changes.

One day Jim came over with a camera and had us prop up some body panels on a chassis and rearrange the shop a few times to give the illusion of an assembly line. Before long, out comes Litestar dealer newsletter #3 December 1982.

It blamed our production problems on Phil Bass and announced Scranton Mfg. Co. as our new manufacturing plant. More promises that demonstrator vehicles would be available by Feb. 1983 with production cars to follow in 60 days.

We still only had one tired prototype and some body panels, but now we were making progress with two half built chassis. The newsletter pictures almost had me convinced there was a production line somewhere.

Don shared my concerns over structural integrity so we loaded the rear half of one chassis with sandbags. Those pictures also showed up in the newsletter and proudly proclaimed " It not only supported the weight, but did so with minimum deflections. They mis-spelled the word minimum it should have said "massive" deflections. Another delay, while we looked for a solution. A simple tension strap arrangement under the engine fixed things.

Oh well.. No more time to test the front half, we were encouraged to "freeze" the design and build some damn cars. This was the only official test I saw up until that point and it didn't take thousands of grueling hours.

Scranton Manufacturing was committed to delivering cars in 2 months. They were shocked to hear we had almost no drawings, because there was almost no design yet. Paul, John, and Irv worked frantically to document what we had so far. We copied nothing from the prototype, so the new car was actually being invented on the shop floor. As soon as I drilled a hole, someone made a drawing and mailed it to Scranton. By the time the mail got there, it was changed three more times. They must have thought we were idiots!

The Big 1983 Chicago Auto Show....

Just as Don was starting to grasp the insanity of this project, Jim threw another challenge at us. In the midst of extreme pressure to build hundreds of cars by yesterday, we were now told to finish prototype #2 in time for the "North American Auto Show". The show was held in Chicago Feb. 1983 and it was just over a month away.

The production thing was just a fantasy, but the auto show was something we could wrap our brains around. Don was eager to prove himself and I had one good fight left in me, so we attacked it with a vengeance. Don was a car enthusiast with high standards and the prototype so far, was quality stuff. We vowed not to embarrass ourselves at this prestigious show by slapping together a piece of junk.

This is the only picture I have of Prototype #2 chassis. Not the round tube construction and aluminum spar. I anticipated making more chassis, so I came up with a jig to hold the parts while I welded them.

I think Paul had moved on to the aircraft project by now. John and Irv were busy making drawings for Scranton, Jed and Tony were busy with something important, so we put Scranton on hold and began a superhuman effort. If nothing else came out of this half baked LiteStar project, we were going to leave behind at least one nice car. I started working 16 hour days to get the body panels mounted, but that wasn't enough, we were going to need help!

Don took charge and found a talented kid from his neighborhood who did spectacular paint jobs. The kid brought his own crew and began the body work while I fabricated parts. Don protected me from interruptions and the other guys hunted down parts and helped when they could. In two weeks we had the body mounted and prepped while I installed controls and wiring. Don was busy finding someone to come in and upholster the interior.

I was too busy to know how he did it, but Don had people coming in at all hours of the day and night just when we needed them. He found a plastics shop that stayed open late one night so we could use their oven to form the canopy and windshield.

The air was filled with adrenaline. Even Jim knew enough to stay out of our way. I think Don stayed late some nights just so I wouldn't have to work alone. I couldn't have worked so hard without support like that.

When all the dust settled, I worked over 350 hours in one month on a fixed salary, and we ended with a 36 hour marathon. Many of the construction details were invented "on the fly" but no serious shortcuts were taken. Instead of slapping together a shell with a nice paint job, we chose to compress three months into one and did the job right. The only compromise was a fake dashboard cover. The car had a stunning white paint job and a beautiful interior. The fit and finish was excellent.

No one thought we would make it and so the display booth was just an afterthought and a serious disappointment. The local dealer brought a tacky homemade sign and the booth was staffed by girls who knew nothing about the car. I was asleep, but heard later that they had 1500 visitors and sold orders for another 300 cars.

This is the Chicago auto show autocycle. Probably the nicest Litestar ever made. I was very protective of this car whenever we gave demo rides or showed it to the public because the paint job was so nice. Anyone know where it is??

It used a Honda 400 automatic and motorcycle wheels.

One day a Dealer showed up with spray cans and proceeded to paint stripes on the car with Jim's permission. It was hard to watch at first, but it actually came out very nice. The solid white was just too plain looking and this was the first car to get any kind of custom graphics. I always thought many people would use the car as a "rolling canvas".

These photo are of the white Chicago Show Car that Doug Walsh built in 1982 for the March 1983 Chicago Auto Show.

The following three photos could be the Chicago prototype:

The following photos were taken at the 1st Dealer Meeting at Innsbrook, MO May 1983.

If you know where this autocycle is, please email steveschmidt at hotmail.com

At the Innsbrook Dealer meeting, we gave demo rides around the property and all three autocycles were overheating badly because they sat and idled while people talked.

We had to rotate them in and do non-stop oil changes because the oil temps got over 420 degrees and broke down the oil causing low pressure.

A rare shot taken during one of our unauthorized after hours test sessions. Note the circular skid marks in the parking lot. These were the only real handling tests performed on the vehicle to my knowledge, and it happened after Scranton started building cars.

We thought it was irresponsible to sell cars without any real dynamic testing, so we took it upon ourselves to do it. We had concerns about weak components and the tests did result in structural failures.

One car rolled over and it started a firestorm of conflicting opinions that ultimately caused Jim Bede to fire us all. We were temporarily hired back to implement some changes that stayed with the car until the end. You could actually say the existing Litestar/Pulse chassis were designed in a few weeks before we left.

The birthplace of the Litestar. Scranton Mfg. was a manufacturer of horse trailers and farm equipment in Iowa.

Excellent management and hard working people still couldn't make the LiteStar project work. The design was just not finished and was changing rapidly as a result of our unofficial testing. Our BD 200 crew practically lived in the factory for two months trying to design the LiteStar on the shop floor. It all could have worked if there was more time and money.

One dealer commented, "we expected hamburger, and you gave us steak".

The satisfaction of our small success was shortlived as we once again faced the growing pressure to mass produce a car that wasn't ready. Satisfaction of a job well done only goes so far.

After working 190 hours of unpaid overtime in one month, Jim Bede still put up a fuss when I wanted to take a week off without pay to recover. He was grateful enough however, to give us both a glowing letter of praise.

I don't know why that project was so important to me? Maybe because I was involved from the beginning. The first year, I worked for just a few dollars and promises of future payment. I found myself making sacrifices I would never make for another job.

The previous year I did well enough roadracing motorcycles, that I was invited to the Grand National Finals in Georgia. I thought work was too important and I didn't go. My two closest competitors went and took first and second in national points. I had an excellent chance of success, but now I will never know.

I also missed family events and birthdays. After all this dedication, I would ultimately get fired and even heard comments that I tried to sabotage the project just because Jim owed me money.

After getting some sleep, I felt better and still enjoyed the lingering satisfaction of a completing a difficult task. I wondered if I was one of those people who needs to be challenged? And if so, then this must be the perfect job. Oh well,.. this paycheck was on time, maybe I'll quit next week?

These were our new orders! The car show was early Feb. 1983 and we spent the rest of the month trying to make the car more production worthy. The show car was still a hand built prototype without any thought given to cost or ease of manufacturing.

We started chipping away at the long list of items we needed to change and parts we needed to find sources for. Things like outrigger wheels, fuel tank, canopy slides steering boxes, lights, seats, etc.

Almost over night, cost became the driving factor behind every decision. Instead of just selecting a suitable part from a catalog, John Kuczaj was assigned the impossible task of finding a steering gearbox for only $25.00. He worked with a gearbox manufacturer for weeks to custom build a stripped down version we could afford. Just when I thought I was done with the fuel tank, someone would hand me a cheaper one and I had to make new mounting brackets.

The drawings we sent to Scranton yesterday would once again be obsolete before they got there. Scranton started to ignore our drawings and improvise. We got their first prototype chassis and it barely resembled ours. We understood their frustration, as they simply were not equipped to reproduce the car. We needed to re-design the car around their manufacturing capabilities, but we didn't know what those capabilities were!

In the meantime, Vaungard of Owosso was spending much time and effort developing a new spray RIM proceess for making body panels. It wasn't fully worked out yet, and we were getting samples that were too heavy, warped, too brittle, too flexible, or all of the above. We mounted our best set of RIM parts on the Scranton chassis and the results were so horrible, even Jim would agree that we can't sell something like that.

Jim was so committed to the RIM process, that it held us back. We could get high quality fiberglass parts in a few days, but were told they were too expensive. We were being buried in defective RIM parts and were choking on the cost restraints, but instead of putting resources into solving these problems (or paying me back) Jim and Stan pulled out all the stops and staged an extravagant dealer show.

The Dealer Show was early in the spring of 1983 and held at a fancy resort near St Louis, MO. We brought the first prototype (yellow car), the second prototype (white show car), and we slapped some primer on the first Scranton chassis with the poor fitting RIM body.

I missed most of the festivities trying to keep all three cars running for demo rides. The new Honda 450 engines ran so hot that the oil would degrade and cause low oil pressure. Fresh oil would cure the problem for another half hour. While one car was being driven, the other was discreetly taken out of sight where I would lay in the hot parking lot, doing hot oil changes.

Don came out to cheer me up by giving me a fancy award that was presented in my absence. It read:

We just laughed thinking we were a long way from reality!

A large group of enthusiastic dealers sat through presentations and slide shows promoting this exciting new form of transportation. Stan did a masterful job of creating the illusion that there was some substance to this idea. Display boards proudly displayed magazines and newspapers from all over the world featuring the autocycle. He talked about huge production volumes, projected sales figures and profit margins. Jim described all the engineering and exhaustive testing that resulted in this safe yet exciting machine.

David Vaughn explained the new RIM plastic that would make high production economical. Scranton promised to meet the growing production demand. There were discussions about insurability and licensing.

It was all I could to to keep from buying a dealership myself!

That evening we sat around the swimming pool and listened to dealers talk about how they refinanced their houses and got loans from friends to buy a dealership. They talked about building fancy new showrooms to handle the flood of eager customers. I had seen all this before and was disgusted, but Don was in a position of responsibility and he was getting visibly ill. The gap between reality and promises was bordering on fraud! Don Rudny was simply too honest to willingly be a part of this and something had to happen. Much of the hype was coming from Stan.

Could it be that Tomorrow Corp., Vaungarde and Scranton Mfg. really didn't know the true status of the project? Could we believe that Jim really thought everything was OK? We thought they all believed what they wanted to believe!

It took some courage, but Don decided to go around Jim and confront Stan, if I would back him up. We both expected to lose our jobs, but we did it anyway.

Shit Hits the Fan

Don communicated our concerns about the design being untested and not ready for production. He emphasized our safety concerns about using stock wheels and brakes on a car weighing 3 times as much. Of course, Stan was shocked! Despite the fact that his son in law works in the shop and has frequent long phone conversations, he sincerely thought everything was on track. He appreciated our candor and encouraged us to come directly to him with any future concerns.

Later we had a polite, but confrontational meeting with Jim and Stan. I remember thinking we were seriously outgunned here. I expected Stan to expertly distort the facts until we happily admitted we were wrong, and Jim would use "Bede Logic" to explain away our petty concerns. To our surprise, Stan seemed almost unbiased and in search of the truth! He carefully extracted our concerns and stuck them right in Jim's face. We held our ground, but in the end it came down to our opinions without any hard evidence versus the infinite wisdom and reassuring words of a famous aircraft designer.

Stan finished with a short pep talk on how we need to communicate better and work together so we can all get rich. Temporarily relieved of that burden, we went back to work feeling we had done the right thing.

Look out.. We're moving in!

We knew it would take extreme measures to save this project, so we decided to move in with Scranton. This allowed us to work more efficiently and bypass all the communication problems. It didn't hurt that we were farther from Jim's influence. We hoped to adapt the vehicle to Scranton's factory first and then document it later. We were wasting too much time with useless drawings. I also hoped we could squeeze in some testing so we could defend ourselves better the next time we disagreed with Jim.

Around that time we hired another full time engineer named Dick Kleber. He had worked on several other specialty car projects, and was familiar with the hype and exaggerated claims, so he came up to speed quickly. He also brought in Bill Molzon, a talented designer and fabricator to help us with the dash board and many other body related issues.

I was starting to breathe a little easier, but the pressure was still on. Over the next few months we rotated in and out of Scranton, keeping 3 or 4 people there at all times. I think we averaged about 8 weeks each, over several months. Scranton put us up in a motel, gave us office space and free run of their trailer manufacturing facility.

We had two of their best shop people and full cooperation from everyone in the place. They genuinely appreciated the work this project could bring them. We responded by working long nights and weekends while trying to adapt the design to utilize the machinery and materials they had on hand.

We reluctantly switched from thin wall round aircraft tubing to mild steel square tubing and included slots and oversize holes to accommodate there working tolerances. Almost nothing was copied from the second prototype, so once again, we had to go backwards before moving forward.

After getting settled in, it became painfully obvious that we were spinning our wheels before. We had flooded them with so many obsolete drawings that they weren't even opening the mail we sent. The only solution was to roll up our sleeves, go out in the shop and build something using their machinery. If it worked, they made a fixture directly off the part and started producing it. If it hadn't changed in a week, someone would document it. Build it first, draw it later was our new motto.

Scranton Litestar was finally taking shape but we needed bodies. Jim finally gave in and let us use fiberglass until the RIM process was worked out.

Bill Molzon came out to create a dashboard and resolve many body details. We were told, he's one of those clever guys that can build anything, anywhere with any materials you have laying around. We put this concept to the test by having him work with fiberglass in cold dark shop with a dirt floor. We gave him one can of bondo and some fiberglass resin, then left him alone for the weekend. The plant manager warned him before he left that a big snow storm was coming. Bill kept working by a small window after the power went out, until the resin would no longer cure from the cold. He them braved an Iowa blizzard to get back to the motel, only to find out the power and heat were turned out. He spent the day in bed wearing his coat to stay warm, but the dashboard was finished when we got there on Monday.

We suffered through marginal working conditions, tight budgets, and the occasional irate dealer who would show up unannounced, looking for the car he was promised six months ago.

More safety concerns.

Scranton had purchased 20 complete motorcycles, and they were determined to use as many parts as possible to save money.

The front suspension (forks) were too tall and we needed to change the steering geometry to lighten the steering feel. On the show car, I solved these problems by relocating the axle midway up the lower fork leg. It worked, but it weakened an already overstressed part. We all agreed that it was a very bad idea to sell cars that way, but there was no alternative short of abandoning the forks for a new design. This was completely unacceptable since there was no hard data to support our concerns.

Don and I still expressed our doubt about the brakes, wheels and suspension being inadequate for the ever increasing weight of this vehicle. I was still racing motorcycles and I saw broken swing arms, burned up brakes and bad wheels just from driving them harder. I was certain these parts would fail on a 900 lb. Car!!

No one was willing to stop production just because some young mechanic had a "hunch: that something would break. Not even if all the engineers agreed with him! Unfortunately, there weren't any finished cars to test yet.

Is it too late for testing?

The yellow car was known to be fragile and was driven accordingly, The white show car was too different to draw conclusions and too pretty to put at risk. We finally got a nearly completed Scranton car back to Mundelein to use as reference for documentation. The car was red and then later painted silver. My impromptu braking test confirmed that the brakes were indeed marginal and if you could get the front wheel to lock up, it chattered violently as the forks flexed back and forth.

When presented with this information, Jim brought in the author of some book on vehicle handling to get another opinion. The author was also an aeronautical engineer, and they became fast friends. After seeing the chatter in action, the author described it as a "judder: caused by too much flex in the forks.

Despite my prediction, the fork legs had not yet broken off where we installed the new axle clamps. Jim maintained that racing brake pads would improve the braking, and there would be no flex problems if we would just reduce the weight! Things were getting tense between Jim and the crew. We didn't want to go over his head again, but things were still being ignored.

More Bede Logic...

I installed racing brake pads and we invited Jim to watch some braking tests. We looked up the D.O.T. test requirements and tried to make it realistic. I couldn't get it to stop in the specified distance, but Jim always could. Everyone noticed that he seemed to be going much slower than I was, so we called him on it.

Things were starting to get ugly now and we asked if Tony could sit in the back seat and watch the speedometer. He again appeared to be going much slower. Tony shrugged and said that, yes Jim had hit the brakes exactly when the speedometer said 40 MPH. Apparently, Jim was taking advantage of Speedo lag to pass the test, and argued that it still followed DOT specs. He was going well above 40 MPH in a low gear and then backing off the throttle, The car decelerated rapidly from engine braking, but the speedo needle dropped more slowly. When the slow moving needle drifted down to 40 MPH, the car was going maybe 30. To Jim it was an acceptable solution for now. Let's just get it in production and then work on the weight problem!

This

is no Sports Car!

We

were stuck with lousy brakes and a chattering front end for now. The next issue

was handling. Figuring I would never get permission, I found a deserted parking

lot, screwed up my courage, and started driving in circles faster and faster.

Hey, someone had to try this before a customer did! The car leaned awkwardly

onto the outrigger and would unweight the rear tire until it eventually lost

traction.

The result was a fairly low speed controllable power slide. I remember thinking Jim would probably call this a speed limiting safety feature if he knew about it. I found a curved road in our industrial park and kept going faster until the rear wheel would slide at 45 MPH. It was actually fun, but seemed to severely limit the cornering speed. That night I drove the same curve in my VW beetle with tall skinny snow tires and went through at 50 MPH thinking "some sports car"!

A week later I followed an empty school bus taking a shortcut through the industrial park and he also went through at 50 MPH. Without sliding. Apparently the only danger is being embarrassed when a school bus passes you in a corner!!

Crash

test Dummies

By

now Jim was sure we were out to get him. At a local airshow he ran into Bruce

Emmons, an engineer who designed an innovative ultralight. Bruce also specialized

in vehicle dynamics so Jim asked him to stop by and take a look at some problems

we were having. I confessed to Don about my unauthorized handling tests and

he must have felt obligated to let Jim know we were going to do more. Bruce

stopped by and Jim sent him over to watch our first official handling tests.

We wanted to demonstrate the fork judder for Bruce, so I drove the red Scranton

car #2 and hit the brakes hard. The front end shook violently and the fork

leg broke off right where I predicted it would. I veered to the left and stopped

in a puddle of fork oil. I guess young mechanics can have accurate hunches

after all. Oh Well,.. we fetched the Scranton #1 car with the RIM body for

the cornering tests. I started by sliding around the parking lot doing figure

eights. It would occasionaly get into a wierd hopping mode while sliding, but

it looked like fun so everyone wanted to try it. Dick Kleber took his turn

with similar results, then Don hopped in. Don got some good speed and made

a very aggressive turn. The little outrigger wheel was overloaded to the point

where it tried to roll sideways off the rim, letting the steel rim contact

the ground. The sharp edge dug a groove in the asphalt and the sudden side

load cause the tension rod to buckle in compression. The outrigger tucked under

and it rolled on its side spilling Don onto the pavement.

Fortunately, it scrubbed off a lot of speed first and Don only suffered minor scrapes. Bruce recalls being overwhelmed by this dismal display of vehicle engineering. He was also a consultant for the big Detroit automakers, and now he was watching a vehicle in the final stages of production being tested for the first time by a handful of guys in a parking lot. Within a half hour, we broke two out the only four running litestars in the world.

The Face Off...

Jim chewed out both of us for breaking half the Litestar fleet, just to make him look bad. Even though we were right to worry about these problems, we somehow became the bad guys for delaying production even more. Well, at least it was no longer "our word against his". These problems were real and even firing us won't make them go away.

Tempers were flaring now between Jim, Stan and Scranton management. After an ugly meeting to stop production, Stan called another meeting at an airport conference room. Don and I were getting sick from all this stress, I think Dick and John were there also.

Stan took charge as usual and once again surprised us by not taking sides with Jim. In fact, he surprised everyone by asking Jim to step aside for the good of the project, and putting Don in charge of further development. Stan must have looked at Bede's history and decided that he is his own worst enemy. All of his projects progress too fast and some ultimately fail. Maybe he stays involved a little too long.

We were asked what it would take to salvage things, and were given the OK to start a crash program to replace the brakes, wheels, tires, and front suspension with stronger components. We agreed to an unrealistic time frame of 4 to 5 weeks. Needless to say the car ride back from the airport was very quiet.

We met the next morning in Don's office for a strategy session. Jim marched in with a big smile and said he wished he could give us all raises, but we were fired instead. John Kuczaj wasn't fired, but he quit in disgust. We wondered why it took so long and actually felt relieved to be free of it.

We all get hired!

Who knows what went on when Stan, Vaungarde and Scranton found out what he had done. I think they all knew the project was in trouble, and we were the only ones trying to save it. Besides it just looked bad to fire us for worrying about safety.

Jim informed us that we were hired back as consultants for one month to do the re-design. We figured Jim probably fired us to assert himself and save face. None of us disliked Jim, we just wanted the LiteStar to succeed.

We all agreed to stay, but now we had an attitude. We no longer asked for permission to do anything and we didn't care how much we spent. We went from fixed salary to hourly pay in anticipation of long hours. We understood Scranton was suffering and just wanted quick "bandaids" to put on their cars so they could deliver them and recover a little money. We did our best to preserve as much of their hard work as possible.

This was a tall order, we needed to wipe out all the problems in one try with no second chance in just four weeks. We had the same people, but now with complete freedom to do it our way. We used off the shelf parts such as car tires, wheels and brakes. We replaced the outrigger wheels with larger units that had a higher load rating, and then added a down stop to prevent "tuck under" I built special hubs and a beefier rear swing arm. We were designed into a corner with the front forks. And I suggested a beefed up version of a 1930's leading link fork. It made a lousy cycle suspension, but it was well suited to a Litestar. It used the same steering pivot and fit into the same space while accommodating the larger wheel and brakes. It also allowed us the freedon to adjust the trail for lighter steering and build in some anti dive.

Bruce Emmons was hired to help us with structural analysis and he recommended tubing sizes and construction methods to handle the loads. We went conservative on everything because we knew this was our last chance.

The Litestar is Reborn!

Geez, this was way too easy! Why didn't we do this two years ago? Everything fell into place, it was robust, easy for Scranton to build and probably cheaper. We did it right in less time than it took to do it wrong! I think we modified the Scranton #2 car (now painted silver), and the last thing I remember is driving it through the parking lot late at night, running over 2x4's to test the suspension. It rode better, handled better, didn't chatter and stopped safely. All without any fuss.

I don't know if Scranton incorporated these changes, but I believe the later Pulse cars used our final design pretty much intact. It didn't turn into the ultimate supercar, and still had many lesser problems to be solved, but we all left feeling pretty satisfied that we made a difference.

Bruce stayed on for a few more weeks and Dave Ulicki was hired to take over fabrication. Bruce investigated the rod buckling problem some more, and made some simple test fixtures to load the outriggers and measure the stresses. He did more useful common sense testing in one week than we did in two years.

Jim still refused to implement his changes, saying "let's get it into production first". This worried Bruce enough that he documented all his testing to protect himself.

Can we do this over?

We should have gotten medals, but we got fired instead. I often try to imagine how it could have been without Jim at the steering wheel. No one can dispute the fact that he comes up with some very exciting concepts and has the amazing ability to package and present them to the public. His name, infectious enthusiasm, and charming articulate personality, seems to attract investors like flies to a fresh paint job. The fact that he exaggerates performance figures and quotes unrealistic prices with impossible delivery dates, guarantees a backlog of orders. All of those things could be excused, if he would just pass the ball to someone who can handle the details and deliver a good product.

I lost touch with the project after we left Scranton, but through the years every now and then I catch a glimpse of this remarkable vehicle in advertisements or on TV, the memories flood back and I wonder.... 'What If'?

Today, I look forward to learning more about Ed Butcher, Dave Vaughn and the other brave souls at the Owosso Motor Car Company who fought as hard as we did to make Jim Bede's dream a reality.

I am amazed how the OMCC group was so isolated from all the previous effort. I guess Jim wanted a fresh start and wasn't really on speaking terms with any of the old crew.

OMCC did a tremendous amount of work to fill out the missing details and convert to a new engine.

The Pulse suspension, brakes, wheels and larger outriggers looks like the stuff we whipped up in the last 4 weeks. If anything OMCC made the chassis more massive and "clunkier" looking, which must have drove Jim crazy. OMCC had to tool up from scratch because the Scranton cars were so diffferent and then turn their attention to all of the little things that had never been worked out.

Not many people could have done what Ed Butcher did in a short time! I could have helped out tremendously in the early stages. David Vaughn was involved even before Scranton and always struck me as a clear thinking person who could get things done.

Paul Griffen would be the leading expert on BD-5 aircraft history. Burt Rutan also worked on the BD-5 and probably contributed more than Jim, to the success it did have? If anybody needs a hero, I recommend Burt Rutan and believe he accomplished 1000 times more than Bede.

There was a fellow named Bob Wagner (I think) that was employed by Jim's cousin and worked on the fan car. We were using his cousins shop space. Bob's background of repairing boats, was a great help to all of us. He showed me the basics of fiberglass, and spent a good deal of time doing the messy work too. One of the other employee's father also came in for a couple nights to help with welding. Of course Paul Griffin spent time in the shop designing as we progressed, and yes,... even Jim Bede would wander in mostly telling jokes, but occasionally getting his hands dirty too. There was one night where everyone stayed late and helped cover the foam body with layers of glass. This misguided attempt to speed things up, resulted in another two weeks being spent sanding and filling the lumpy surface created by a bunch of amateurs. What a circus it was sometimes!!!!

The End.

>

Today,

Doug lives in southern Michigan and spends his free time wrenching on motorcycles.

His insight into the development of a 'Timeless Style' automobile is truly

an amazing story....

one

man's dream....and another man's ability to build it.

After leaving Bede, Doug started a business with Don Rudny called Practical Innovations. They designed and built all kinds of industrial prototypes and vehicle stuff. Also did a lot of work for Bruce Emmons including a protoype space frame chassis for a GM car code named P2, that later became the Fiero.

Doug then moved to Detroit and worked for "Turbo Components" developing aftermarket turbo kits for cars. Bruce Emmons started "Autokinetics" and Doug stayed with him for 6 years building automotive prototypes. Some interesting projects were a stainless steel sports car chassis and a high performance outboard motor mount/steering system for boats.

Doug even built a running car engine with an 18 lb. space frame engine block.

In 1992 Doug wrote a small book about vacuum forming plastics for the hobbyist. This allowed him to quit work and manufacture small machines out of his home for three years.

He then designed larger vacuum forming machines, and today sells construction plans and parts for people who want to build their own.

In 2000, Doug returned to off road motorcycle riding and racing after a 20 year lay off. He also enjoys whitewater kayaking.

Even

though many people lost money in the wake of the entire Litestar / Pulse project,

over 360 vehicles were built and many Owners Club members today agree....

"Its

a blast to drive" and "It draws attention like nothing else".

These Scranton built vehicles can be identified by the small wheels, with the outrigger tension rod fix, and bent square tubing frame around the engine. Scranton originally purchased 20 bikes and we used their first car as a test mule.

The vehicles described below are the only cars built by myself at Bede Design, and I can positively identify any of them if they are found.

The first autocycle was the prototype BD-200. This car shares no parts with any other car.

The second autocycle was the Chicago auto show car which had a TIG welded round tube chassis attached to the front and rear of the main aluminum tube. It used one of the first two hand laid fiberglas bodies made from new molds. It also had custom seats, no exposed outrigger link, motorcycle forks and wheels, 450 automatic, small outrigger wheels, and an aluminum dash. It was white in color with a three color stripe.

The third autocycle (chassis only) I built used round tubing, and a GPZ 1100 donor bike. It belonged to a dealer (Dave Scwartz), and it was later fitted with the spare set of hand lay-up body parts that we got to build the show car with. I don't know if it was ever completed.

There was also a test car that used the very first Scranton built chassis. It started with a red paint job, but was later painted silver. This was the car that we used to develop the new suspension and car wheels/brakes right before I left Bede Design. It had the first prototype larger outrigger wheels, and I believe it was used after we left, for outrigger testing by Bruce Emmons. I dont know if that car was ever titled or sold. It can be identified by a nicer quality TIG welded front suspension, and volkswagen wheels and tires.

Below, Instrument panel shows 1984 Honda 450 - Hondamatic instruments.

Below, view of floor and under dash, old type cassette player and the #2 stenciled onto the center frame?

"Why not drive the car of Tomorrow....Today"

More about the BD-200 - Original Autocycle Plans